Visto que las interfaces-controladoras de DAW-mixer las han desdoblado para pasar la parte controladora de DAW a un iPad...mis opciones se reducen a Presonus AudioBox 18VSL o la MOTU Ultralite pagando salidas que no utilizare...pero bueno....quizá estan tambien en las ultimas de mantenimiento

Interfaces de audio: como los tiempos que corren, mierda

OFERTAS Ver todas

-

-29%UA Apollo x6 Gen2 Essentials+

-

-5%Kawai ES-60

-

-19%Behringer X-Touch Compact

A propósito de viajes inter-estelares... Realmente, cual interface o conversor trabaja a 24 bits? ninguno, verdad? si por cada bit son 6 dB de Rango Dinámico, para 24 Bits seria un total de 144 dB... el único convertidor que conozco que llegue a los 120dB (máx. que he visto) es el Motu HD 192. Que cosas...

#302

Un poco más allá de los 120...

http://www.lynxstudio.com/product_detail.asp?i=59

http://mytekdigital.com/products/stereo192adc.htm

http://mytekdigital.com/products/8x192adda.htm

Un poco más allá de los 120...

http://www.lynxstudio.com/product_detail.asp?i=59

http://mytekdigital.com/products/stereo192adc.htm

http://mytekdigital.com/products/8x192adda.htm

CamiloSalaA escribió:A propósito de viajes inter-estelares... Realmente, cual interface o conversor trabaja a 24 bits? ninguno, verdad? si por cada bit son 6 dB de Rango Dinámico, para 24 Bits seria un total de 144 dB... el único convertidor que conozco que llegue a los 120dB (máx. que he visto) es el Motu HD 192. Que cosas...

Hola CamiloSalaA,

En principio todos los convertidores de 24bits trabajan a 24 bits, otra cosa bien diferente es si todos son capaces de proporcionar el rango dinámico que hipotéticamente una señal de 24bits es capaz de proporcionar en base a su ruido residual en su etapa analógica.

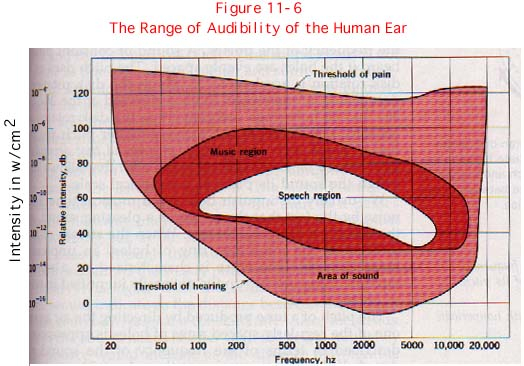

En realidad desde el punto de vista de la calidad de audio, como tal no es necesario emplear 24bits, ya que 144dB de rango dinámico es una medida muy superior a la de nuestro propio rango dinámico auditivo

por otro lado hay varias paradojas respecto a todo esto como las que se relatan en este interesante articulo:

Alguien escribió:

Is Bits Really Bits

I promised I’d talk about the nature of digital signals this month, as part of my on-going discussion of the nature of audibility. Specifically, I want to take a fresh look at the resolution of such signals, and what happens to them in the “real world.” There are some interesting problems with what we have wrought.

First, a quick review. In the digital realm, using our beloved linear pulse code modulation system (LPCM), signal amplitude is represented by a range of binary numbers. The apparent “resolution” of the signal is the ratio between the biggest and smallest numbers in the system. Happily, it is easy to express this resolution in decibels of dynamic range, to wit: each binary bit represents a power of 2 and approximately 6 dB of dynamic range. A 4-bit signal (24, or 16:1) has a dynamic range of 24 dB, while a 16-bit signal (216, or 65,536:1) has a dynamic range of 96 dB and a 24-bit signal (224, or 16,777,216:1) has a dynamic range of 144 dB. You know all this, right? And it’s obvious – 24-bit has way more resolution than 16-bit, right? It has 256 times as much resolution, to be specific. Awesome!

These numbers are abstractions, however, and have no fixed relationship to physical reality. And the way we have implemented the relationship between the virtual and actual worlds leads to not one, but two, BIG problems. So, we need to consider how these ratios are related to the physical world.

First off, these ratios are linked to the analog electronic realm through A/D and D/A converters. Analog signals, of course, are two-dimensional maps of changing energy over time. The maximum amount of energy that can be expressed in any such map is constrained by the limits of the power supply used for that analog circuit, so that the peak-to-peak amplitude of any sine wave cannot exceed the voltage available from the power supply. Skipping over the math, this means that a +/-18 Volt power supply (the most typical case) will yield a maximum signal level of 12.7 Volts RMS or 20.3 dB above 0 VU referenced to +4 dBu.

When we convert that amplitude to binary numbers, the converter is designed so that said amplitude equals the largest signal the digital system can handle. This is a signal that uses ALL of the bits in the digital word (in a 16-bit system, for instance, swinging all the way between 1111111111111111 and 0000000000000000 for positive and negative peaks). We re-name this digital magnitude 0 dB Full Scale (dBFS). This seems like a reasonable and common-sense thing to do. We fix the maximum analog amplitude to equal the maximum digital amplitude. Cool!

But let’s consider what happens at the Least Significant Bit end of the system. In a 16-bit system, the smallest magnitude that can be represented (excluding the effects of dither) is 1/65,000th of the maximum signal, or equal to roughly .2 milliVolts (-72 dBu). When we increase the resolution of the signal to 20 bits, we don’t change the magnitude of 0 dBFS, all we do is push the magnitude of the Least Significant Bit further down toward the grunge and noise floor, so that for a 20-bit word, the LSB is equal to .012 milliVolts. We’ve increased the overall magnitude of the signal by only .18 milliVolts! Going to 24 bits from 16 bits only gains us .2 milliVolts of signal resolution!!

So, we’re increasing resolution at the vanishingly small end of things. No wonder we have trouble hearing it! Increasing resolution in terms of these micro-Voltages makes an increasingly vanishingly small difference. Whew!

Meanwhile, we haven’t bothered to hang on to our “0 dBFS = +20 VU” headroom standard. Instead, we’ve let our nominal level creep upward to as high as –10 dBFS, and sometimes we even master CD pop releases with nominal levels as high as –4 dBFS. In this extreme case our nominal RMS signal level, at the output from a digital console whose electrical specification is that “0 VU = +4 dBu = -20 dBFS”, is a whopping +20 dBu (7.75 Volts RMS)! Hot!!! The implications of this are that (a) we’ve thrown away headroom, and (b) that when we subsequently attenuate this overly hot signal on its way to the loudspeaker (as we most definitely will), we shove those bits even deeper into the analog grunge ‘n noise.

There’s a second problem we have to face as well. We do our listening to acoustic signals, not analog electrical ones. And the relationship between 0 dBFS/+24 dBu electrical levels and X dB SPL acoustical levels is not fixed in any reasonable way. The result has come to be a serious loss of auditory resolution. Consider the following.

If we accept –10 dBFS/+14 dBu as a “nominal” electrical signal level (and we have in practice done almost exactly that), this becomes the level we use to determine the acoustic playback level. For production work, we can assume that level is probably something like 85 dB SPL (it’s the film standard, for instance). That means that the 16-bit noise floor will be at –1 dB SPL, or just below the formally accepted “threshold of audibility” of 0 dB SPL. All well and good, I guess. However, the 20 –bit signal’s noise floor will be at –25 dB SPL and the 24-bit version’s floor will be at –49 dB SPL! Definitely inaudible to us humans. All this is exacerbated by the fact that the acoustical noise floor of the playback room can reasonably be expected to be at or above +40 dB SPL, which means that we can expect masking noises to be running some 90 dB HIGHER than our 24-bit noise floor.

So, we have a serious mismatch of reference levels here, and it unreasonably diminishes any benefit we might expect from the enhanced resolution of 20 or 24-bit digital signals, relative to our venerated 16-bit signal. Failure to reasonably manage the relative headroom of analog and acoustic realms vis-a-vis our digital signal has painted us into a serious wastage of dynamic range. It also means that the resolution benefits of 20-bit and 24-bit signals are not only hard to hear, they’re, well, inaudible as we currently do it. Uh-oh!

Next month we’ll take a similar look at the bandwidth issue. Thanks for listening.

David Moulton

Moulton Laboratories

http://www.moultonlabs.com/more/bits_really_bits/

En definitiva, el motivo de emplear convertidores de 24bits es para poder disponer de un headroom adicional y el motivo de emplear archivos de 24bits o incluso de mayor cantidad de bits (32bits coma flotante) es para disponer de un margen adicional que evite la distorsión en el procesado, y amplié el "headroom" interno de los sistemas de mezcla digitales.

Pero a priori una señal de 16bits es mas que suficiente para representar sin problemas el rango dinámico de cualquier audio analógico, y por lo tanto las diferencias entre convertidores, y máxime cuando todos ellos son capaces de rangos dinámicos cercanos a los 120dB son simplemente despreciables.

Un saludo

distante® escribió:Que tal aguanta el driver la grabación multicanal?

Hola Distante,

Después de probarlo (grabar varios instrumentos con los previos de la UR824 utilizar sus dos mezclas de cascos independientes y conectado a otro interface por ADAT del que se enviaba y recibía audio), puedo decir que estupendamente

Un saludo

A800MKIII escribió:Hola Distante,

Después de probarlo (grabar varios instrumentos con los previos de la UR824 utilizar sus dos mezclas de cascos independientes y conectado a otro interface por ADAT del que se enviaba y recibía audio), puedo decir que estupendamente

Un saludo

Epa! Gracias A800MKIII, la quiero usar para grabar 16 canales simultáneos brindando 3 mezclas estéreo, dada tu experiencia ahora si la compraré a ojos cerrados.

A800MKIII escribió:En definitiva, el motivo de emplear convertidores de 24bits es para poder disponer de un headroom adicional

Hombre, esque yo creo que precisamente lo bonito de los 24bit frente a los 16bit es ese headroom del que hablas, segun lo describes parace que no tenga mucha importancia en el sonido. Yo creo que si queremos ser realistas, como ese articulo prentende ser, hay que tener en cuanta el comportamiento real de una seccion analogica de un convertidor. Mola mucho que el ruido de cuantizacion este bien por debajo del umbral de ruido de la seccion analogica y te puedas permitir grabar con mas headroom, sin usar, de esta manera, los ultimos 3/6dB de la seccion analogica, cosa bastante recomendable tal y como suenan las secciones analogicas de la inmensa mayoria de convertidores en estos ultimos dB de la escala. Asi que en la practica yo si creo que hay una diferencia de 16 a 24, que con 24 puedo grabar mas bajo sin tener ruido de cuantizacion y que por lo tanto suene menos distorsionado al no llevar cerca de saturacion la seccion analogica, aveces pienso que con la mayoria de convertidores del mercado el nivel nominal deberia ser 0dBu en lugar de +4dBu

Yo creo que es genial estar limitado por los 120dB de rango dinamico de la seccion analogica y no por los 96dB de la cuantizacion a 16Bit.. joer! son mas de 20dB de rango dinamico de los cuales se pueden usar unos cuantos para dejar headroom y aun asi todavia tendremos otros cuantos dB por debajo que seguiran haciendo mas silenciosas las grabaciones en 24bit que en 16bit.

Yo creo que usando los convertidores de 24bit como se usaban los de 16bit no habra mucha diferencia, ya que las secciones analogicas de los AD/DAs no han cambiado tanto, pero si se usa el headroom extra de los convertidores de 24bit para no trabajar tan cerca del clip. (salvo distorsion creativa) , yo creo que hay una diferencia notable, sobre todo grabando material con mucha dinamica como la clasica o percusiones. Ademas yo creo cada dia son mas los tecnicos que son conscientes de ello.

Lo que es curioso es ver como la mayoria de convertidores AD y DA tienen un nivel de entrada/salida mas bajo que la mayoria de outboard o previos cuando yo creo que deberia ser al contrario. Es dificil ver un convertidor que alcance los +24dBu mientras que en previos y outboard es bastante normal llegar a +29dBu y unos cuantos cacharros pasan de +30dBu.

saludo

Hilos similares

Nuevo post

Regístrate o identifícate para poder postear en este hilo